On June 27, 2023, a judge of the High Court of Namibia, Ramon Maasdorp, ruled that the Southern African country’s Minister of Mines and Energy, Tom Alweendo, did not have the authority to revoke a twenty-year lithium mining license the ministry had issued to Chinese-owned lithium prospecting, exploration, mining, and processing company Xinfeng Investment.

The company drew international attention when the country’s local daily, the Namibian Newspaper, published an expose revealing underhanded dealings between government officials and the Chinese mining outfit.

The report detailed corruption at the ministry of mines in regard to how the company acquired the mining license, misrepresentation regarding how it conducted its business, and a community push-back against environmental damage and displacement of small-scale miners in the mountainous Erongo region, an area renowned for its rich mineral endowment that includes tin, tantalum, fluorite, and the new kid on the block, lithium.

Lithium as a critical component in the manufacture of batteries for electric vehicles and solar panels to facilitate the green (clean) energy transition has aroused international interest with Namibia sitting on millions of tons of lithium ore, according to a study conducted by the Federal Institute of Geosciences and Natural Resources (BGR) in collaboration with the German Cooperation (GIZ) and Geological Service of Namibia within Namibia’s Ministry of Mines and Energy. GIZ is one of Namibia’s most notable development partners.

At an estimated 9.3 million tons, Chile is said to have the largest lithium deposits in the world. Australia is the globe’s largest supplier.

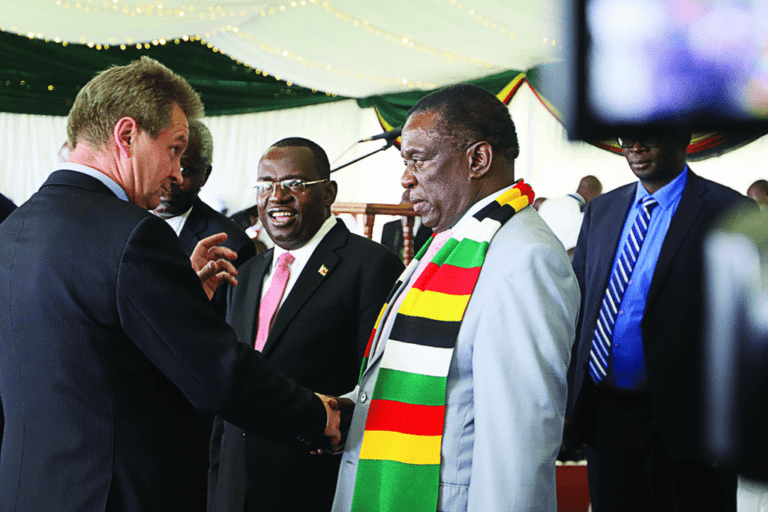

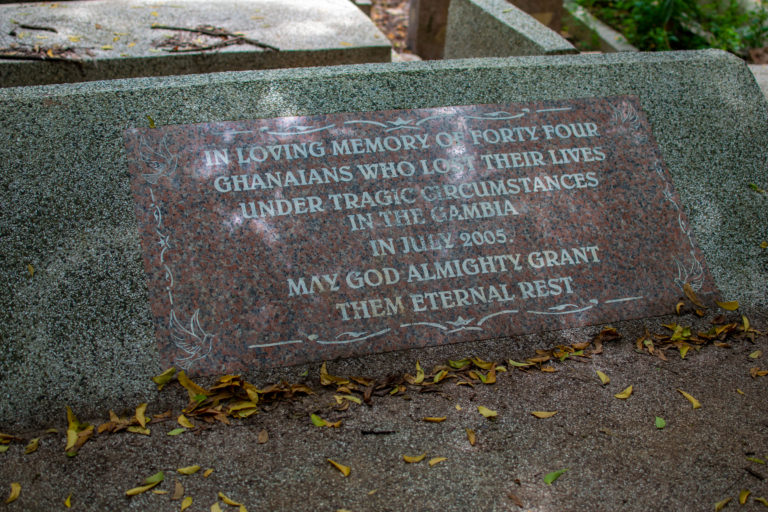

On the African continent, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Ghana, Mali, Namibia, and Zimbabwe hold the largest lithium deposits, according to the British Geological Survey Report of 2020/2021, with mines producing millions in tons of the mineral output in all five countries.

China is the world’s largest importer of lithium ore, and the Asian giant controls over half of the world’s lithium processing and refining capacity.

Although the country has lithium deposits of its own, it does not have the required deposits to fulfill its industrial needs. This makes countries like Namibia essential to meeting local demand.

Towards the end of 2022, a major political storm erupted in Namibia. Namibian authorities stopped tipper trucks carrying lithium ore that were traveling towards the harbor town of Walvis Bay because they lacked the necessary export or transport permits.

Increased attention to the company’s dealings led to allegations of bribery regarding the way the company acquired mining rights in the first place. A local businessman laid charges of fraud against his business partners, whom he accused of fraudulently stealing his mining claims by forging signatures while he was recuperating from injuries sustained in a car accident. He said his claims were subsequently sold to Xinfeng for USD 2.77 million.

The Minister of Mines and Energy then instituted investigations and found Xinfeng guilty of fraud and misrepresentation in the way it acquired the mining license. He (the minister) subsequently revoked the company’s license, which prompted Xinfeng to approach the High Court to have the license reinstated on an urgent basis.

In his ruling, the judge found that “the first respondent proved prima facie that the applicant committed fraud in the process of applying for the mining license.”

But he also found that “the first respondent did not have the power to revoke the mining license without the express or implied authority to do so under the governing legislation but was required to approach a court for appropriate relief.”

In summary, although the Chinese outfit did break the law and the minister proved it, under Namibian law, the minister does not have the power to revoke a mining license, but he has the power to issue it, a victory for the Chinese.

Environmental Concerns

Among those opposed to Xinfeng’s lithium interests in Namibia are the inhabitants of the local community of Uis, a settlement with an estimated population of 3600 inhabitants. Here, locals eke out a living through the trade in semi-precious stones, which are found in abundance in the area. With chisels and hammers, they pound away in the glaring sun to make a living for themselves and their families.

A kilogram of rocks is sold to polishers for as little as USD 2, sometimes even less.

The tourmaline, topaz, and quartz crystals are handcrafted and sold as jewelry, with pieces selling for as much as USD 41 for a necklace or a ring.

These small-scale miners have since been displaced to make way for Xinfeng.

The heavy machinery, which includes tipper trucks and huge excavators, has incensed community activists like Jimmy Areseb, who accuses the company of disregarding local beneficiation and policies adopted by the state to ensure that local communities benefit from the exploitation of mineral resources in their constituencies.

“There was no consultation that took place with the indigenous inhabitants of this area before these Chinese people were given the green light to start their mining operations; these people do not have the necessary environmental clearance to mine in such an ecologically sensitive area. The area in which Xinfeng is mining lithium is a conservancy, and the community used to benefit from trophy hunting concessions. The area also used to be a breeding ground for hyenas, rhinos, and springbok, and when their activities began, the animals moved away because of the lithium extraction methods such as blasting,” Areseb lamented.

Michelle Maletsky and her husband Harold are generational inhabitants of the Uis settlement. They say their parents and grandparents all made a living from the mineral endowment of the area as small-scale miners, and they had just been awarded a mining claim in the Uis area to upscale their activities when they got a shock on December 16, 2022.

They said that on December 16, 2022, when they went to the site where their mining claims were, they were not allowed to enter the site. The road had been barricaded with an entrance, and the security personnel at the gate told them they were not allowed to enter.

“My husband and I, we registered at Mines and Energy, we paid, we did everything like Mines and Energy told us, and then one day, when we checked on the system (online) of the Ministry of Mines, our claims were taken off. Then we went to the site to put up our boards (that show ownership of the mining claims), but the Chinese were fighting us; they told us no, we cannot enter the area because they bought the area for a lot of money and nobody is allowed to go in there,” Maletsky said.

Meletsky says her family has lost their means of making a living as a result of the displacement, and she and other similar miners with mining claims in the area are looking at different avenues to regain their lost claims, but this is proving to be difficult.

Conclusion

The rush for lithium has taken the dynamic of accusations of corruption, bribery, and underhanded dealings by Namibian government officials, but it has also brought hope for its green energy proponents, who believe that electric batteries will assist in reducing the globe’s carbon footprint.

Namibia, Zimbabwe, the DRC, Ghana, and Mali—can they supply the globe’s appetite for lithium? The answer is yes.

But at what cost?